The Language of Querying an Agent

Before we start this week, a brief announcement:

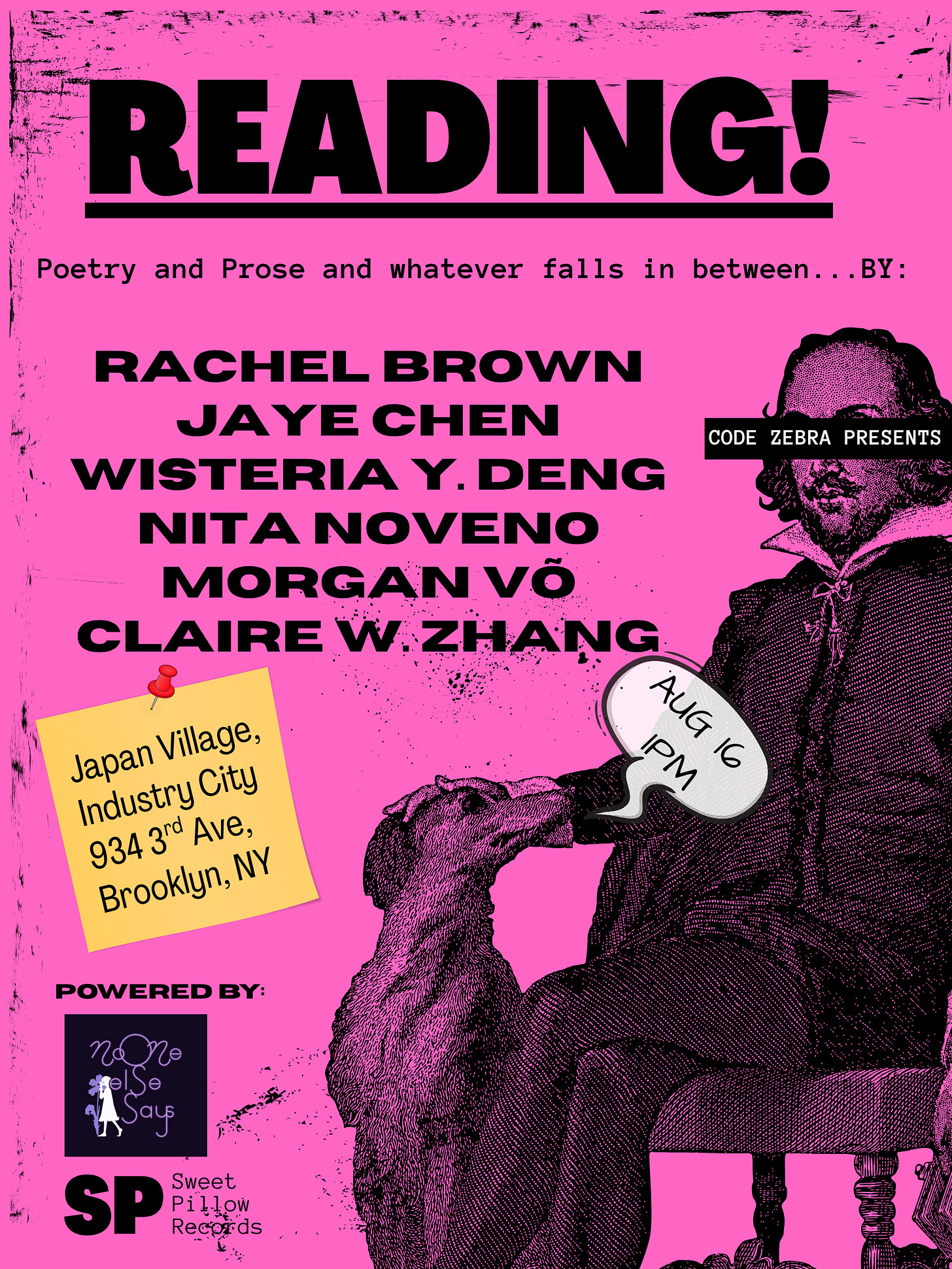

In the spirit of our earlier call to “become an influencer within your own circle of friends,” Claire W. Zhang—founding member of Beyond Craft—invites you to a Brooklyn reading she’s organizing on Sat, 8/16 at 1PM, part of a free indie music festival with a killer lineup.

We’re bringing together writers fr…